The whole family went to see Jacques Tati’s Mon Oncle at the IU Cinema. A pretty robust crowd for 3 pm on a beautiful Saturday. In the introduction, it was mentioned that we were about to see the dubbed-English version; you could hear actual mais non!s from the audience, but then the speaker trumped us by pointing out that it was the Jacques Tati estate itself that chose the English-language version to restore. I found this intriguing and counter-intuitive, and/but I have to say that the English dubbing made a certain sense to me — it underlined the movie as international, part of a global modernism. Also, the movie has very little dialogue, so it’s close to a silent movie (albeit one in which sound if not language plays a key role).

The movie is so great! I had never seen it. The plot, such as it is, involves a few days in the life of the Arpels, husband and wife; he the boss of a plastics factory, she a housewife in a squeaking rubber house-dress, their son Gerard, and their semi-bohemian — or at least poor and unemployable — uncle/brother, M. Hulot (Tati himself), whom M. Arpel sets up with a job in his factory. (This does not go well, in ways that evoke Chaplin’s Modern Times: a kind of Sorcerer’s Apprentice-like struggle with the factory ensues). The movie is all about a clash between the forces of mid-20th-century-industrial modernity, planned culture, the plastic pipes manufactured by M. Arpel’s factory (shade of The Graduate — “plastics” — we don’t know what these rather perversely-coiling red tubes are actually used for), futuristic (Jetsons-like) gadgets, plants contorted into artificial shapes in the garden, and a top-down, status-oriented professional-managerial class that oversees these regimes of order, on the one hand; and on the other, everything associated with Mr. Hulot, the shambling, messy, wandering, erring, foggy-headed uncle filled with a spirit of improvisatory play who rides a rickety bike everywhere and lives in a shabby boarding house. (We see him ascending the irrationally non-linear stairs to his room in a cut-away shot, bowing and dodging to avoid neighbors and hanging laundry.)

The girls seemed to enjoy it quite a bit too, seeming to relish all the weirdly hilarious, subtle physical comedy: the dolphin fountain which only goes on for high-status visitors; the absurd winding paving stones in the Arpels’ front yard; the comedy of the broken water pipe; the food carts, the boys who whistle at people to make them walk into signs, and the hilarious little gang of dogs racing through the movie as a force of aleatory randomness. Tati’s argument for chance and play is enacted in the filming of the dogs; Tati seems just to have let them go and tried to follow their crazily-criss-crossing itineraries as best he could. The movie’s anti-industrial/modern themes sound a bit obvious or even smug, but it all plays out brilliantly and surprisingly. The movie feels like a Rube Goldberg device, a hyper-stylized, perfectionist contraption (the sounds and the score are amazing). It’s one of the most stylized and amazingly-designed movies I can think of, up there with The Umbrellas of Cherbourg — there’s a certain irony in that, of course, given the ways the movie always seems to favor “nature” over artifice.

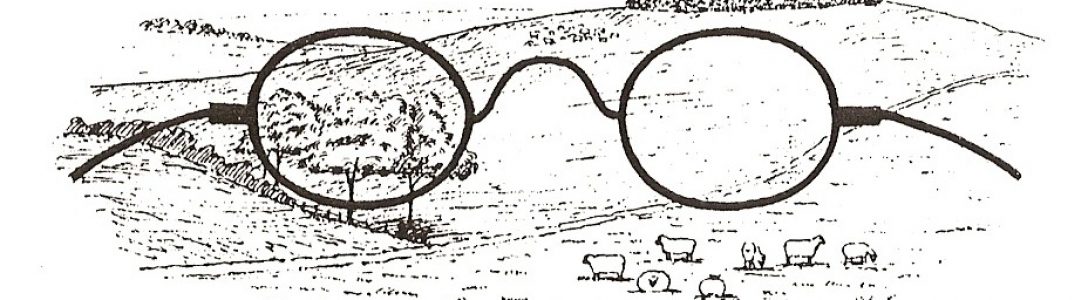

This was maybe my favorite scene (on the bottom), when the Arpels accidentally lock themselves in their laser-motion-detector garage and are trying to convince the dog to walk through the beam to trigger the door. (There are a number of shots in which round windows appear, with heads at the center, like giant eyeballs.)

The dogs are allied with the wayward boys whom Gerard falls in with when he can, to escape his parents’ oppressive oversight: swarms/packs of unruly creatures defying rules of order, propriety, and linear movement. (Wiki tells us that, interestingly, “At its debut in 1958 in France, Mon Oncle was denounced by some critics for what they viewed as a reactionary or even poujadiste view of an emerging French consumer society, which had lately embraced a new wave of industrial modernization and a more rigid social structure” — I did not know that term, poujadiste: “Poujadism was opposed to industrialization, urbanization, and American-style modernization, which were perceived as a threat to the identity of rural France.”)

This is way better than a brick & mortar esnmblishaett.

I probably watched this movie 30 years ago when I was 5 years old and just remember few things as dolphin fountain when opening for status of visitor or two circle windows look like eyes in the night. It was really fun for me at that time and tried to search several times the name of movie through few scene remainder in my mind. Finally found on this site via right keywords. Wanna watch like my 5 years old. Thank you 🙂